By: Tynesia Boyea-Robinson

History is complicated because it reflects the thoughts, beliefs and perspectives of the storyteller. American History is particularly fraught because it has far too often erased the narratives of the people most central to the country’s founding; indigenous Native American people and enslaved Africans and their descendants. Black History month is a peculiar and important answer to this profound historical erasure, a catch-all time of the year when we lift up and celebrate the stories that often aren’t told, and sometimes forgotten.

This type of erasure is something experienced by most people of color at some point in their lives. I have grappled with erasure many times in my life, but none as stark as my experience while touring the Decatur House, the first private home in the White House neighborhood, built in 1818. The White House Historical Association hosted our guided tour as part of the kickoff week of the Presidential Leadership Scholars program. I was excited to join the fourth cohort of 59 leaders from across the country, chosen for their commitment to community service and bipartisanship.

My classmates and I meandered through the impeccably preserved home, learning about the storied lives of the Decaturs, and the myriad of foreign and American dignitaries including Henry Clay, Martin Van Buren and Edward Livingston who inhabited the residence over the generations since our country’s founding. Our tour guide was deeply well versed in the history of the property owners, the art hanging on the walls, and even the furniture and fixtures. But as we followed her down a narrow staircase and walked gingerly into a seemingly forgotten room towards the back of the home, I tensed up, sensing where we were. I asked with some trepidation, “What was this room used for,” and braced myself for the answer.

“This was the slave quarters, “but we now use it for our ongoing educational program for surrounding schools.” My throat tightened and my senses heightened, as often happens when you experience the effects of erasure. Several of us were sitting uncomfortably in diminutive backless stools, akin to preschool chairs, in tight rows in the narrow space. Several of my classmates peppered the unassuming tour guide with questions ranging from surprise that slavery existed in the North in an urban setting to curiosity about the number of “slaves” who lived in a room this size. Shortly into the conversation, the tour guide was both fatigued with the line of questioning and had exhausted her knowledge of the subject matter. Looking around the room, one of my colleagues joked that the space was about the same size as a row house for staffers in DC.

I shuddered. People say it is difficult to hate up close, and I would argue that it is equally difficult to love in secret. How can you love ancestors when their contributions are at best joked about and at worst denied? How do you believe that their stories matter—that your stories matter—when those histories are not respected? I glanced at my fellow black scholars whose pained faces mirrored my own. Instead of speaking up, we sunk lower in our seats, conditioned to accept the erasure, and whispered only to one another of our pain in the shadows.

Yet then something happened. As our tour guide rounded up our class to move to the next section of the house, Alanah Odoms, a New Orleans civil rights lawyer who champions justice in her personal and professional life, pulled the person who made the joke aside. The pair trailed behind the group as Alanah shared gently but firmly why the comment was offensive. I hovered within earshot as I witnessed two things that would change me forever. The first is that Alanah was not shackled by silence. She unapologetically imparted our shared truth of outrage from a place of confidence and care. The second was that our colleague was receptive to the feedback and listened with a spirit of learning and humility.

How was it possible that these two strangers could openly engage with each other on a topic that I so often avoided in unfamiliar and unstructured environments? I learned the hard way that when you raise issues of race without support or infrastructure, the end result is too often dismissal and exclusion—or, I am quickly labeled an angry black woman.

Yet I took inspiration both from Alanah and the untold stories of my ancestors and made a decision. At our large group conversation about the tour, I asked my fellow scholars to join together and ask the White House Historical Association (WHHA) to document and memorialize the history of enslaved people at the Decatur House.

Once I spoke my truth, I was shocked at how quickly our class sprung to action. Alanah spearheaded an effort to engage board members armed with research provided by Isabel Gonzalez, an influential author and editor. Mary Reding, a tenacious attorney dedicated to gold star families, and Brian Wolff, a prolific energy advocate and philanthropist, led fundraising. Dr Loren Robinson and Dr Christina Grant, who at the time were both transforming Philadelphia through health and education respectively, devised a curation and education strategy. Together we made the case for WHHA to establish a dedicated exhibit and resources to support the restoration of the neglected “slave” quarters at the Decatur House coupled with interactive educational materials for the public.

Eight months after our visit to Decatur House, the WHHA completely transformed the slave quarters to capture the stories of enslaved Americans and their role in the White House neighborhood. And almost two years to the day, WHHA announced their new initiative, Slavery in the President’s Neighborhood.

We often want to tie stories like these up in a bow by congratulating ourselves for what we achieved and glossing over the challenges along the way. I would argue that succumbing to the instinct to distill and oversimplify creates the enabling conditions for perpetuating our culture of erasure. In my professional life, I provide organizations with tools to rewire this instinct.

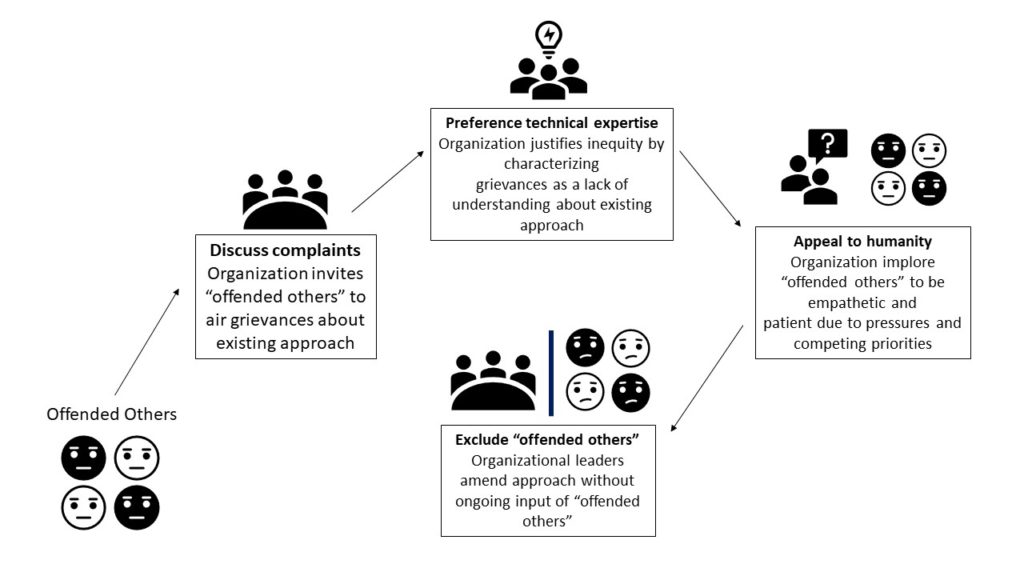

My day job is helping institutions rebuild their approach to capitalism to achieve social impact and racial equity. As you may imagine, this type of work often results in tense interactions. Our work with WHHA was no different. I’ve learned that instead of litigating the past, it is often more helpful to highlight the patterns across similar work to enable behavior change. Most organizations confronting inequity and their role in perpetuating it experience a range of emotions that result in unproductive interactions. The diagram below captures the four typical reactions.

It is the rare organization that produces quality results once they reach step four. And even when they do, the gravitational force of erasure is unrelenting even in very supportive and progressive environments. What this looks like in practice is lauding the White House as the symbol of freedom and power while suffocating the stories of Americans who have neither. The difference, as is the case with so many things, is leadership.

These barriers can be overcome when leaders like WHHA President Steward McLaurin take risks on a new project; when visionaries like Secretary of Smithsonian Dr Lonnie Bunch create historical monuments that are beautiful because of their balance of pain and possibility; and when 59 strangers can unite in service of lifting every voice. I wept when I entered the slave quarters in Decatur House and as I read the names of my ancestors who contributed to building this country. Together we had broken the shackles of silence. And in one small pocket of our nation’s celebrated and paradoxical journey, black history was finally synonymous with American history.